At Mamoni village in Rajasthan's Baran district, preparations for Holi begin days in advance, and with lots of anticipation. The celebration itself lasts for as long as a week in March, usually at the time of the full moon. For people of the village, this religious festival is a time to express gratitude to god and nature before the harvest season sets in. Baran is among the poorest districts of Rajasthan.

The night before Holi, a fire is lit to symbolise, the legend says, the burning of Holika. Wheat stalks are roasted on the fire. In earlier times, villagers greeted each other by smearing rakh or ash on their faces the following day. As time passed, people replaced ash with coloured powder, which is now used everywhere in the country to celebrate this festival.

Holi may have a strong religious significance but for the farming community, the festival is the harbinger of spring and the harvest season. Among other things, it brings joy and hope.

Sita Mehta, a farmer from Mamoni, has made miniature buffaloes out of cow dung to pay homage to the gods that have kept her and her family, and their cattle, safe. The installation comprises a large buffalo, smaller ones drinking at a water source, and grass as their food. There is also a small replica of Lord Krishna.

Baran is home to the Sahariya tribe, one of the most deprived communities in Rajasthan. The Sahariyas originally settled in the forests of what is now eastern Rajasthan (then in neighbouring Madhya Pradesh). The elders of the community remember the time when their grandfathers foraged in the jungles. Things changed, they said, when people from other states came to grab their land and shunted the inhabitants from their own home. The forests now belong to the government.

The Sahariyas never practiced agriculture, always living in and caring for the forests. This community had invaluable knowledge about medicinal and edible plants, and kept their own cultural practices alive. But when the Sardar, Jat, and other powerful communities moved to the areas, they enforced their norms and practices of farming as a way to keep the Sahariyas powerless.

Gradually, the governments cut down the jungles under the Indian Forests Act (of 1927) to make more room for conventional farms, and the Sahariyas found themselves being used as cheap or free labour for the new landowners. Without any access to the jungles, the Sahariyas lost many of their traditions and social systems. Most of their old food sources also disappeared. The situation is grim in areas like Kishanganj taluka, where cash debts are being held over the Sahariyas as leveraged threats. The Bonded Labour (Abolition) Act of 1976 does not seem to protect the community.

I spent the Holi harvest festival with the Sahariyas, who have been working as bonded labourers for powerful farming landholders for decades. During the week-long festivities, the community gathers together every evening to sing and perform in plays. The first day of the festival is dedicated to food, family and prayer.

The festival is not complete until the elders make a small pilgrimage to a nearby temple that was built in praise of Lord Hanuman and a local saint, Siddh Baba. The elders of the community pray for the safety of their homes and a good harvest. Earlier, all the men would join the elders and head to the temple together, singing along the way and praying all day long. Today, they lament that the number of people visiting the temple has been dwindling over the years, and are worried that traditions will be lost with the coming generations.

Devilal Sahariya, a senior member of the community, is a farmer and folk musician, who sings and play the drums along with others. He has been fighting a losing battle to hold on to his land. “The courts and the government have been asking us to provide proof that the land has been ours for the last three generations. How can we prove that with a written document? Can jungles be owned?” The Forest Rights Act (FRA) of 2006 sought to reverse the colonial notion of the State as owner of the forests. But getting the forest administration and bureaucracy to follow it on the ground hasn’t been easy.

The government had allotted Devilalji 20 bighas (or 10 acres of land) under a state government scheme, but presently he only has access to 12 bighas. The rest of the land is under the control of someone else, a member of an upper caste. Although the government allotted him the land, he said, he has no document to prove it. “We can eat the food we grow on our land, but we have no say on what happens to the rest, where it goes or for how much," Devilalji adds, "We don’t want our children to have the same fate as us.”

According to Meenal Tatpati, a member of the non-governmental organisation, Kalpavriksh, “The FRA attempts to undo the historical injustice towards communities like the Sahariyas by seeking to recognise the rights of the local communities over forest land. It allows for the land claimed to be free of all previous encumbrances and procedural requirements, including leases under any state or central government law."

However, she says, during the initial years of the FRA's implementation in Rajasthan, communities were asked to provide signatures of several officials, including the forest department, to corroborate their claims. "The officials do not exercise control over the local processes, but instead assume that the forest department will take responsibility. For the communities to file claims over their land, and then to exercise control over it, there needs to be an empathetic approach towards them, which seems to be missing in officials. There is a need for the state government to take urgent action to expedite the processes under FRA and help communities like these to secure their land – the source of their livelihood.”

People from local organisations believe that the Sahariyas are perceived as weak because they do not use force to affirm their rights on the land. For decades, the villagers have been exploited and have been living in perpetual fear that their land or homes might be snatched away from them. The Sahariya community first came to the attention of activists because of a the prevalence of acute hunger in the district around 2002. Children of the community were malnourished and dying.

Devilal says NGOs have been providing support to the community in taking legal action for their land rights, but their efforts have not been too successful. Others in the community recount similar stories. At the end of our meeting, Devilal insists that I go back to his home the following day to celebrate Holi.

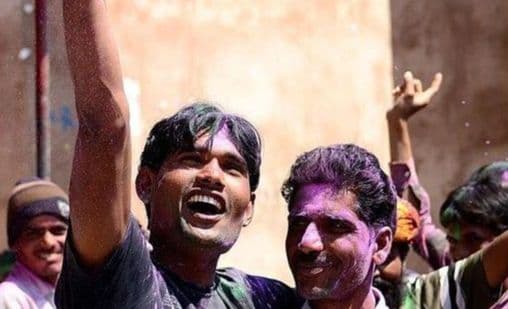

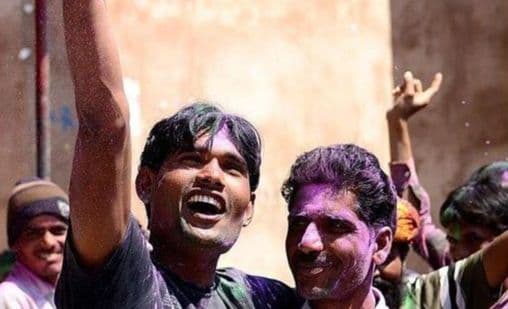

The next day, everyone is all set to play with colour. Joy envelops the community and children see it as an excuse to be at their naughtiest. The elders say that the celebrations have got more aggressive with time. For them, Holi still remains a way to give thanks before the harvest.

Meanwhile, the Sahariyas’ future remains uncertain. Planning for their children’s future is getting increasingly difficult with no access to their land or proof to show it is theirs. 'Achhe din' have not reached the people of Baran.

Colour is smeared on faces, water is splashed everywhere

Children use new tricks and start playing in muck

There is no place for novices. Holi is the one day where even beating someone with a stick is allowed

I made the mistake of asking the boys to show me their coloured hands, and then they got clobbered!

*****

The term 'Holi' comes from 'Holika' – according to legend, , the name of the evil sister of the demon king, Hiranyakashap. He was the all-powerful king of Multan, and a devotee of Lord Vishnu, who granted him a special boon as reward for his devotion. But his special powers made him arrogant. He regarded himself as god, and made all those in his kingdom regard him in the same way. But his own son Prahlada remained devoted only to Lord Vishnu. In rage, the king subjected his son to cruel punishments, but Prahlada did not change his mind. Finally, the story goes, Holika, Prahlada’s aunt, tricked him into sitting on a wood pyre with her, while she wore a fireproof shawl. However, when the fire started, the shawl flew away from Holika and got wrapped around Prahalda, and she was killed. Lord Vishnu then appeared and killed King Hiranyakashipu. The next morning, people from the kingdom took ash from the fire and applied it to their foreheads, as a way to remember that good triumphed over evil.

Special thanks to: the Sahariya community; Kapil Jain; Raju Mehta; Vishal Singh.

At Mamoni village in the district of Baran, Rajasthan, preparations for Holi begin days in advance, and with lots of anticipation. The celebration itself lasts for as long as a week in March, usually at the time of the full moon. People of the village use this religious festival to express gratitude to God and nature before the harvest season sets in. Baran is among the poorest districts of Rajasthan.

The night before Holi, a fire is lit to symbolize, as the legend goes, the burning of Holika. Wheat stalks are roasted on the fire. In earlier times, villagers greeted each other by smearing “rakh” or ash on their faces the following day. As time passed, people replaced ash with coloured powder, which is now used everywhere in the country to celebrate this festival.

Holi may have a strong religious significance but for the farming community, the festival is the harbinger of spring and the harvest season. Among other things, it brings joy and hope.

Sita Mehta, a farmer from Mamoni, has made miniature buffaloes out of cow dung to pay homage to the Gods that have kept herself, her family and cattle safe. The installation comprises a large buffalo, smaller babies drinking at a water source, and grass as their food. There is also a small replica of Lord Krishna.

Baran is home to the Sahariya tribe, one of the most deprived communities in Rajasthan. The Sahariyas originally settled in the forests of what is now eastern Rajasthan; neighbouring Madhya Pradesh. The elders of the community remember the times their grandfathers foraged in the jungles. Things changed, they said, when people from other states came to grab their land and shunned the inhabitants from their own home. The forests now belong to the government.

The Sahariyas never practiced agriculture; always living and caring for the forests. This community had invaluable knowledge about medicinal and edible plants, and kept their own cultural practices going. But when the Sardar, Jat, and other powerful families moved to the areas, they enforced their set of farming knowledge and practices as a way to keep the Sahariyas powerless. Gradually, the governments cut down the jungles under the Indian Forests Act to make more room for conventional farms, and the Sahariyas suddenly found themselves being used as cheap or free labour for the new owners. Without any access to jungles, the Sahariyas now lost many of their traditions and social systems. Most of their traditional food sources also disappeared. The situation is grim in areas like Kishanjangh Taluka or block, where cash debts are being held over the Sahariyas as leveraged threats. The Bonded Labour (Abolition) Act of 1976 does not seem to protect the community.

I spent the Holi harvest festival with the Sahariyas, who have been working as bonded labourers for powerful farming landholders for decades. During the weeklong festivities, the Sahariya community gathers together every evening to sing and perform in plays. The first day of the festival is dedicated to food, family, and prayer.

The festival is not complete until the elders make a small pilgrimage to a nearby temple that was built in praise of Lord Hanuman and a local saint, Siddh Baba. The elders of the community pray for the safety of their homes and a good harvest. Earlier, all the men would join the elders and head to the temple together, singing along the way and praying all day long. Today, they lament that the number of people visiting the temple has been dwindling over the years, and are worried that traditions will be lost with the coming generations.

Devilal Sahariya, senior member of the Sahariya community is a farmer and folk musician, who sings and play the drums along with other members of the community. He has been fighting a losing battle of holding on to his land. “The courts and the government have been asking us to provide proof that the land has been ours for the last three generations. How can we prove that with a written document? Can jungles be owned?” The Forest Rights Act 2006 sought to reverse the colonial notion of the State as owner of the forests. But getting the forest administration and bureaucracy to follow it on the ground hasn’t been easy.

The government had allotted Devilalji 20 bighas (or 10 acres of land) under the state government scheme but currently he only has access to 12 bighas. The rest of the land is under the control of someone else, a member of an upper caste. Although the government allotted him his land, he said, he has no document to prove it.

According to Meenal Tatpati, a member of the NGO, Kalpavriksh, “The FRA attempts to undo the historical injustice committed towards communities like the Sahariyas by seeking to recognise the rights over forest land for the local communities. It allows for the land claimed to be free of all previous encumbrances and procedural requirements, including leases under any state or central government law. However, during the initial years of its implementation in Rajasthan, communities were asked to provide signatures of several officials, including the forest department over their claims, so that they could be accepted. The officials responsible do not exercise control over the local processes but instead assume that the Forest Department will take responsibility. For the communities to file claims over their land, and then to exercise control over it, there needs to be an empathetic approach towards them, which seems to be missing in officials. There is a need for the state government to take urgent action to expedite the processes under FRA and help communities like these to secure their land-the source of their livelihood.”

Devilalji continued to explain, “We can eat the food we grow on our land, but we have no say on what happens to the rest, where it goes or for how much. We don’t want our children to have the same fate as us.” People from local civil organisations believe that the Sahariyas are perceived as weak because they do not use force to affirm their rights on the land.

The Sahariya community first came to the attention of activists because of serious hunger issues in Rajasthan around 2002. Children of the community were malnourished and were dying. For five decades, the villagers have been exploited and have been living in perpetual fear that their land or homes might be snatched away from them. Devilal softly spoke about how the NGOs have been providing support to the community in taking legal recourse, but their endeavours have been met with little success. Other members of the community had similar stories to recount. At the end of our meeting, Devilal insists that I go back to his home the following day to celebrate Holi.

The next day, people are all set to play with colour. An air of joy envelopes the community and children see it as an excuse to be at their naughtiest.

Colour is smeared on faces, water is splashed everywhere.

Children use new tricks and start playing in muck.

There is no place for novices. Holi is the one day where even beating someone with a stick is allowed.

I made the mistake of asking the boys to show me their colored hands, and then they got clobbered!

The elders say that the celebrations have got more aggressive with time. For them, Holi still remains a way to give thanks before the harvest.

Meanwhile, the Sahariyas’ future remains uncertain. Planning for their children’s future is getting increasingly difficult with no access to their land or proof to show it is theirs.

Achhe Din have not reached the people of Baran.

A Small Story

Holi, comes from “Holika”, the name of the evil sister of the demon king, Hiranyakashap. He was the all-powerful, invincible King of Multan, and a devotee of Lord Vishnu. Lord Vishnu granted him a special boon as a reward for his devotion, but his special powers made him arrogant. He regarded himself as God, and made all those in his kingdom do the same. But his own son, Prahlada, remained devoted only to Lord Vishnu. In rage, the king subjected his son to cruel punishments, but this did not make Prahlada change his mind. Finally, as the story goes, Holika, Prahlada’s aunt, tricked him into sitting on a wood pyre with her, while she wore a fireproof shawl. However when the fire started, the shawl flew from Holika and got wrapped around Prahalda, and she was killed. Lord Vishnu then appeared and killed King Hiranyakashipu. The next morning, people from the kingdom took ash from the fire and applied it to their foreheads, as a way to remember that good triumphed over evil.

Special Thank You:

The Sahariya Community

Kapil Jain

Raju Mehta

Vishal Singh